Relationship between AASI, hypertension, and left ventricular hypertrophy in pediatric kidney transplant patients

Aesha Maniar1, Lynn Maestretti1, Jami Steger1, Ruby Patel1, Paul Grimm1, Abanti Chaudhuri1.

1Pediatric Nephrology, Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford, Palo Alto, CA, United States

Ambulatory arterial stiffness index (AASI), derived from ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), reflects arterial stiffness via blood pressure fluctuations over 24-hours. AASI correlates with pulse wave velocity, a marker of arterial stiffness and cardiovascular risk. However, data on AASI in pediatric and transplant patients are limited.

A single-center retrospective chart review of pediatric kidney transplant recipients (2017–2023) with post-transplant ABPMs and echocardiograms was performed. Analyses included t-tests, Spearman correlation, and multivariable regression.

The study included 78 patients (mean age 14.9 ± 4.40 years); 50% (n=39) were male, and 86% (n=67) had deceased donor transplants.

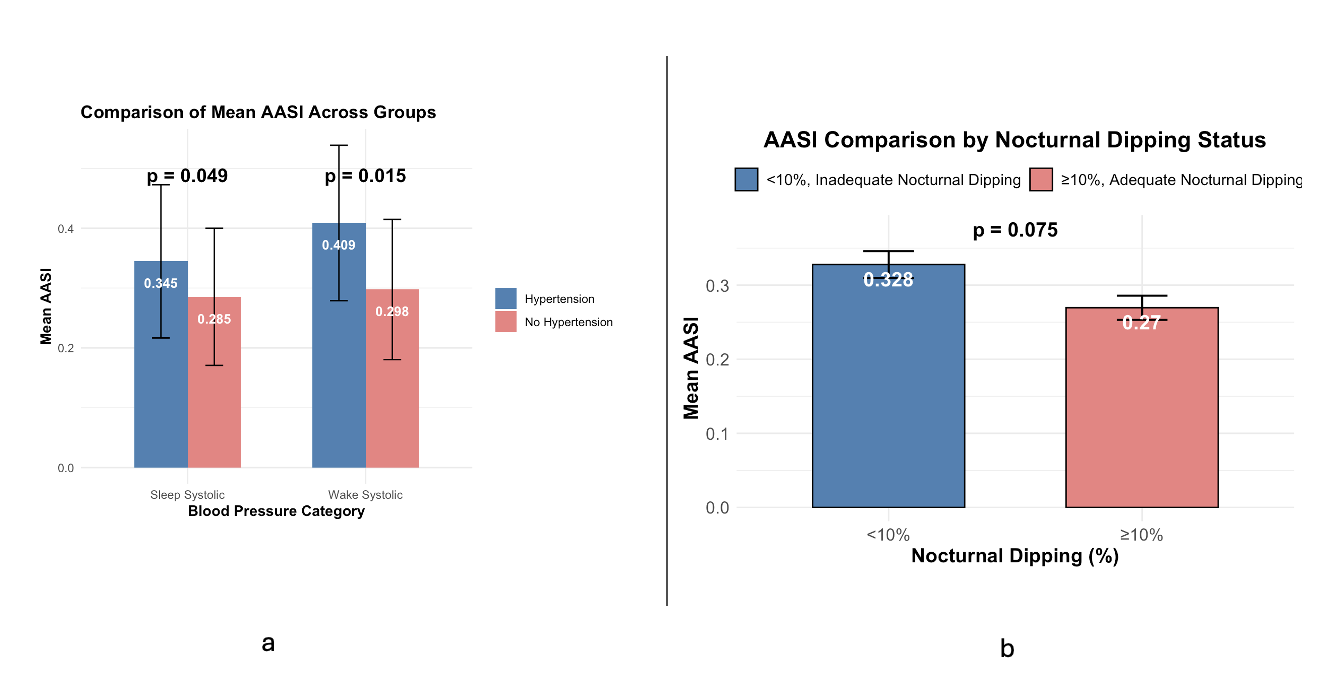

Higher AASI associated with wake and sleep systolic HTN compared to those without hypertension on ABPM (Fig 1). AASI was 0.409 ± 0.130 in patients with vs. 0.298 ± 0.117 in those without wake systolic HTN, p = 0.015. Sleep systolic HTN group also had higher AASI, 0.345 ± 0.128 vs. 0.285 ± 0.115 those without HTN, p = 0.048. No significant associations were found between AASI and diastolic hypertension. In multivariable regression, wake SBP remained a significant predictor of AASI (β = 0.396, 95% CI: 0.236–0.554, p = 0.043).

AASI was higher with inadequate (<10%) nocturnal dipping (ND) (mean AASI = 0.328 ± 0.135; n = 55) than in those with adequate (≥10%) ND (0.270 ± 0.078; n = 23), with a trend toward significance (p = 0.075) (Fig 1).

There was no difference in AASI between those with and without left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH); mean AASI was 0.326 ± 0.135 in the no LVH group (n = 44) and 0.279 ± 0.109 in the LVH group (n = 16) (p = 0.279). Spearman correlation between AASI and LVMI was non-significant (ρ = -0.13, p = 0.34). In multivariable regression, higher AASI was associated with lower odds of LVM (OR = 0.0011, 95% CI: 0.0001–0.58, p = 0.036). Male sex linked to higher odds of LVH (OR = 6.88, 95% CI: 1.56–30.45, p = 0.013), and lower wake systolic percentile to decreased odds of LVH (OR = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.003–0.56, p = 0.021). Age was not significant (p = 0.57).

AASI was associated with systolic HTN and inadequate nocturnal dipping but did not show a strong relationship with LVH or LVMI. The paradoxical link between higher AASI and lower LVMI/LVH may reflect timing of echocardiography relative to ABPM. Longitudinal studies may determine whether persistent AASI elevations contribute to cardiac remodeling and adverse outcomes.

[1] blood pressure

[2] AASI