Social drivers of health and pediatric kidney transplant outcomes: a PEDSnet study

Ashton Chen11, Nhat Nguyen1, Ally Zelinski1, Michelle R Denburg1, Mark M Mitsnefes2, Bradley P Dixon3, Anne Dawson5, Tahagod Mohamed5, Caroline Gluck6, Jodi Smith7, Joseph Flynn7, Marva Moxey-Mims8, Ruby V Patel9, Leyat Tal10, Priya S Verghese4.

1Children's Hospital of Philadephia, Philadelphia, PA, United States; 2Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, United States; 3Children's Hospital of Colorado, Aurora, CO, United States; 4Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States; 5Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH, United States; 6Nemours Children's Hospital Delaware, Wilmington, DE, United States; 7Seattle Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA, United States; 8Children's National Hospital, Washington, DC, United States; 9Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, United States; 10Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX, United States; 11Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, United States

Introduction: Social drivers of health (SDoH) impact health equity and patient outcomes. The impact of SDoH on pediatric kidney transplant recipients is not well understood. We investigated the effect of SDoH on patient and graft survival in youth with a kidney transplant.

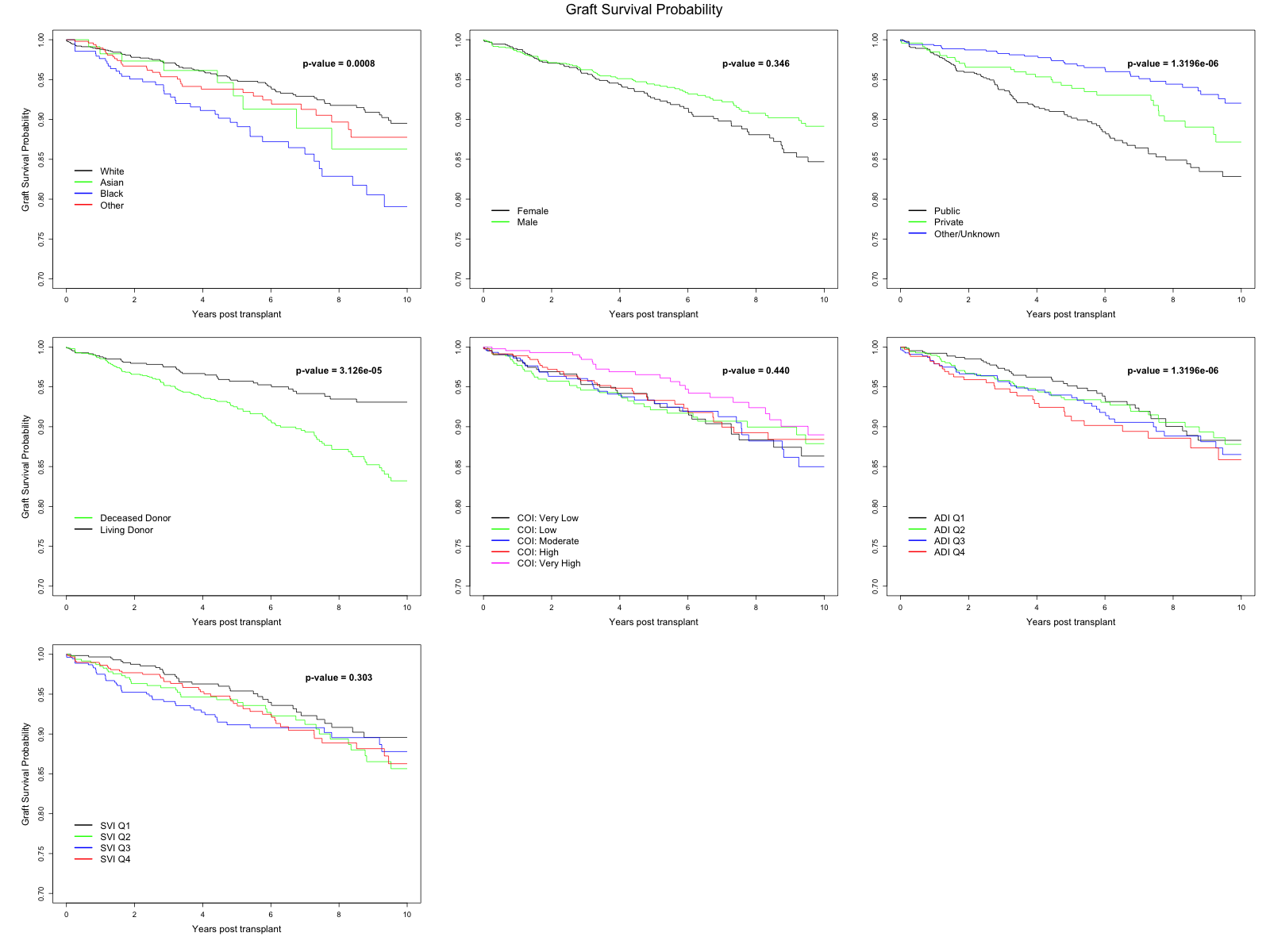

Methods: In a multi-center retrospective cohort study, using the PEDSnet learning health system, data were extracted from the electronic health record using bioinformatics methods. Inclusion criteria: youth 0-21 years old who received a primary kidney transplant between 01/01/2009 – 03/31/2024 with census tract data available. Patients with multi-organ transplants, missing donor information, or those with incomplete follow-up data were excluded. Exposures were language, insurance type, distance to transplant center, area deprivation index (ADI), social vulnerability index (SVI), and child opportunity index (COI) including education and social/economic domains. Primary outcomes were patient survival and graft survival. Adapted Kaplan-Meier estimates for SDoH exposures were used for graft survival. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models estimated associations of exposure with outcome.

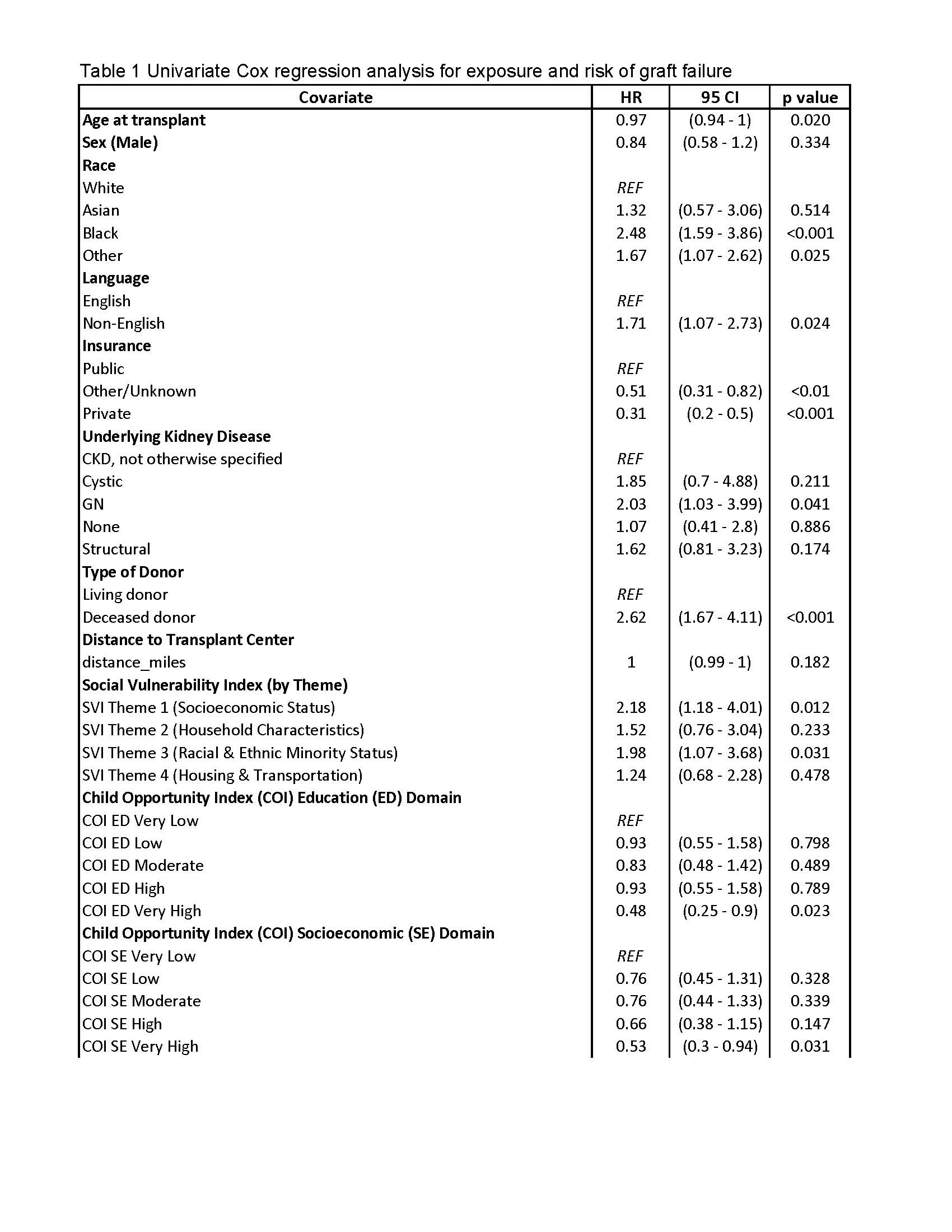

Results: Of N=2,351 transplant recipients: 41% were female; 37% had a living donor; median age at transplant was 13.3 years [IQR 7.1,16.7]; median follow-up was 5.4 years [IQR 2.8, 8.7]. Overall patient survival at 1, 3, and 5 years was 99.6% (95%-CI: 99.3, 99.9), 99% (95%-CI: 98.6, 99.9), and 98.5% (95%-CI: 97.9, 99.1) respectively. Overall graft survival at 1,3, and 5 years was 98.7% (95%-CI: 98.2, 99.2), 96.3% (95%-CI: 95.4, 97.1), and 94.1% (95%-CI: 93.0, 95.2) respectively. In univariate Cox regression analysis, non-English language, public insurance, greater distance to the transplant center, higher ADI, lower COI, and higher SVI were not associated with lower patient survival. Kaplan-Meier estimates for SDoH exposure and graft survival are shown in Figure 1.

Non-English language, public insurance, and lower COI were associated with increased risk of graft failure in univariate Cox proportional hazard model with death as competing event (Table 1).When SVI was categorized into themes, Socioeconomic Status (Theme 1) and Racial & Ethnic Minority Status (Theme 3) were associated with 2-fold higher risk of graft failure (Table 1).

Conclusion: SDoH were not associated with patient survival. However, SDoH related to socioeconomic vulnerability, lower education opportunities, and minoritized groups were associated with increased risk of allograft failure in pediatric kidney transplant recipients. There is opportunity to improve allograft survival and health equity for youth with kidney disease through qualitative work and rapid development and implementation of patient level interventions within the learning health system.

[1] Patient Survival

[2] Allograft Survival

[3] Social Driver of Health

[4] Kidney Transplant

[5] Health Equity