Early Australian experience with APOLT in children with metabolic liver disease

Isabela Santos1, Kiera Roberts1, Michael Stormon2, Susan Siew2, Samuel Elison3, Arthavan Selvanathan4, Mathew George1, Gordon Thomas1.

1Department of Pediatric Surgery, Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia; 2Department Gastroenterology, Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia; 3Department Gastroenterology, Women and Children’s Hospital Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia; 4Genetic Metabolic Disorders Service, Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia

Introduction: Auxiliary Partial Orthotopic Liver Transplantation (APOLT) emerged emerged in the 1980s as a surgical alternative for the treatment of acute liver failure (ALF). The impending development of gene therapies for inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) has stimulated the use of APOLT as a safe liver transplant alternative for IEM, with the future possibility of graft removal and cessation of immunosuppression.

Our unit is the only centre in Australia performing APOLT. Following success with its use in children with ALF, we recently expanded this application to include children with IEM. The objective of the present study is to review our early results with APOLT for children with IEM and to report some technical aspects of the procedure that have helped achieve success in our limited series.

Methods: Retrospective review of two patients with IEM who had APOLTs in our centre in the last six months.

Results: Patient 1 (aged 2.5 years) with Propionic Acidemia (PA) and patient 2 (aged five years) with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTC) were referred for liver transplantation after continued metabolic decompensation despite maximal medical management.. They both received left lateral segment grafts from deceased donors.

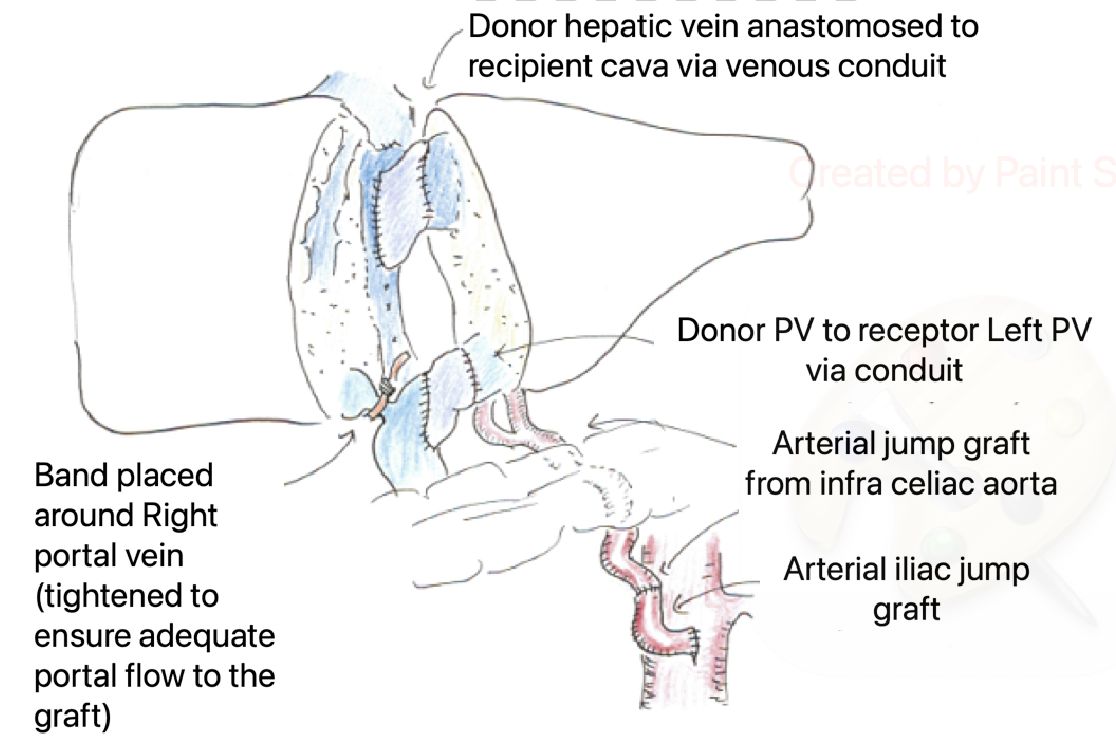

The surgical technique in both patients included native left hepatectomy and caudate lobe excision to expose the native cava. Caval and portal vein (PV) clamping was avoided by using side-biting clamps and placing extension vein grafts from the cava (for the graft hepatic vein) and main portal vein (for the graft PV), prior to implantation. These techniques improved patient stability with minimal physiological disruption and limited blood loss. Following implantation, narrowing of the native portal vein was done using pediatric pulmonary artery bands till portal flow volumes to the transplanted graft was greater than to the native liver. Arterial inflow into both grafts was using conduits directly from the aorta.

Both patients recovered well post-transplant with good graft function and no vascular complications nor rejection. Whilst follow-up duration has been limited thus far (six and five months respectively), neither patient has had further metabolic decompensation, despite substantial dietary protein liberalization.

Conclusion: Based on our early experience, we believe APOLT is a feasible and safe strategy for children with IEM. The use of deceased donor grafts with the ready availability of vessels for reconstruction is an important advantage. The use of flow volume measurements to modulate PV flow appears to be effective. Further studies are needed to assess the long-term outcomes of APOLT for IEM, in particular the role of gene therapy.

[1] APOLT

[2] Liver transplant

[3] inborn errors of metabolism

[4] Surgical technique